The call of the open road beckons to electric car owners now that Washington and Oregon have completed their portions of the West Coast Electric Highway, a network of rapid recharging stations to enable long distance electric-powered travel.

The system could eventually stretch from British Columbia to Baja California. The far end for now is in Brookings, just north of the Oregon-California border. We sent our correspondent out on a road test.

My highway road test began at an Enterprise car rental lot in the Portland city center, one of the very few places in the Pacific Northwest where the average Joe can rent an all-electric vehicle.

Rental agent Mina Oleiwan set me up in a 2015 Nissan Leaf.

"The best thing about this Nissan Leaf is that it actually tells you how many miles you have left. You don't really have to worry about it," Oleiwan said.

Asked if the car can make it all the way to Oregon's southern border, she answered with a laugh: "You let me know."

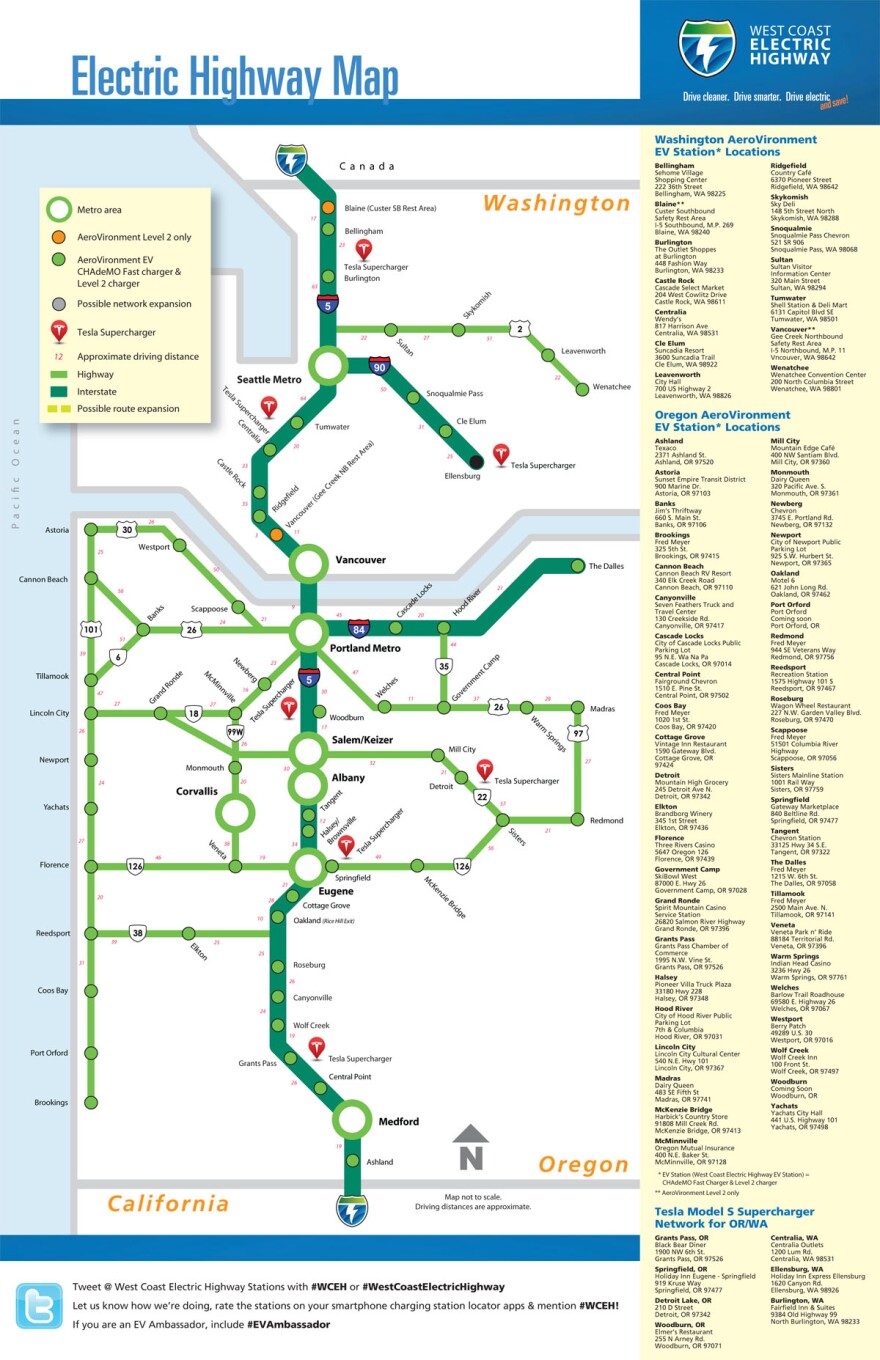

At the start of the journey, I felt a little nervous about going on a 330 mile road trip using an electric car with an advertised range just over 80 miles. But I downloaded a smartphone app (called Plugshare) to help me find the nearest charging stations. For extra security, I also printed an old-fashioned map of the West Coast Electric Highway and its rapid charging network.

And with that, I hit the road. The well-engineered car and the charging aids quickly inspired confidence.

American taxpayers shelled out more than $5 million dollars to plan and build this network, with 56 public fast-charging stations spaced about 25 to 55 miles apart along key north-south and east-west highways in western and central Washington and Oregon.

Combating 'Range Anxiety'

The object is to facilitate longer trips between or beyond major metro areas, where many recharging options already exist. That's supposed to make non-polluting electric cars more attractive to more drivers.

One of the challenges in building the green highway was finding property owners along the routes to host the rapid recharging stations.

In Elkton, Oregon, Brandborg Winery co-owner Terry Brandborg said he was won over.

"We were a little bit skeptical because we only have eight parking spaces and we gave up two for this," he said. "But the first folks that came in and used it walked into our tasting room and ended up joining our wine club. So I went, 'Hey, this works out OK.'"

Other fast chargers are located at highway gas stations, park and ride lots, restaurants and tribal casinos.

A private company named Aerovironment operates the charging network and bills users for each fill-up or by monthly subscription.

I chose the "unlimited" charging plan, which costs $20 per month. The subscription easily paid for itself just in my two-day trip in the Leaf. A comparable gasoline-powered rental car would have consumed around $55 in fuel for the same round trip to Brookings and back.

Aerovironment sends a little electronic key fob to new subscribers. When I pulled up to one of the company's bright green and silver charging pillars, I waved this key fob in front of the machine. Once it recognized me, I would lift the heavy DC fast charging cable, plug it into the Nissan LEAF and sit back while the car battery refilled.

The high-power rapid chargers typically refilled my battery to 80-85 percent level in 20-25 minutes.

Brief Hiccup Before The Finish Line

Generally, the system worked nicely except for one brief scare in the coastal hamlet of Port Orford, when a charging station crucial to my trip temporarily malfunctioned. The charger recognized I was plugged in and ready to charge, but would not cough up any electrons.

I called a toll-free number to reach a customer service tech who did a remote reboot of the high-tech rapid charger. In minutes, I was back in business.

An hour down the road, I spotted the 'Welcome to Brookings, Oregon' sign. Elated, I consulted the trip computer, which showed 330 miles, five recharging stops and a little over ten hours of elapsed time.

On my return trip, I turned inland at Reedsport and checked out some of the charging spots on the I-5 corridor. I stopped seven times to recharge on Day 2, including one more encounter with a seized-up charging station which was fixed with a phone call. The multiple recharging stops added about three hours each way to the cross-state trip.

"I congratulate you," said Tonia Buell, who coordinates the West Coast Electric Highway at Washington State's Department of Transportation. "That is quite an adventure that you took. It's rare for someone to use so many stations in a day."

When I suggested that the pace of my trip made the system best suited to leisure travel, Buell pointed out that current electric highway users include commuters and business people, in addition to leisure drivers.

She said she's impressed to see use of the system climb, and noted that the charging stops give people plenty of time to catch up on their texting.

"The ones along I-5 are getting used quite often. Sometimes there is a line of vehicles waiting to charge up," Buell said. "Some of the east-west areas, like along US 2, those see a lot more use in the summertime, when people are out doing their summer vacations and traveling."

The system is working well, she continued. "We have a lot of positive feedback. We have national and international interest in the West Coast Electric Highway. This is the biggest tri-state, tri-country project. Ultimately, it is going to go 1,350 miles all the way from British Columbia, Canada to Baja California, Mexico - or BC to BC."

Expansion Plans

Currently, there is a big gap in the fast charger network between the Oregon-California border and the Sacramento area. The California Energy Commission is expected to put out a solicitation in the coming months to build out the Northern California portion.

WSDOT has sketched out plans for filling gaps and expanding the network, too. The Washington portion of the West Coast Electric Highway includes 12 rapid chargers, compared to the 44 in Oregon's portion of the network. WSDOT recently published an "Electric Vehicle Action Plan" which proposed to extend the electric highway eastward to Spokane from CleElum and Wenatchee.

But Buell said those ambitions are unfunded at this moment.

State transportation departments report more than 12,300 plug-in electric vehicles have been registered in Washington and more than 5,500 in Oregon. In Idaho, where much less public charging infrastructure exists, the state has registered fewer than 200 electric vehicles.

On my drive to Brookings, I did not see another electric vehicle once I left the Portland metro area. I had no competition to plug in to those charging stations - which were so critical to making the trip - until the very last recharging stop in Woodburn, Oregon, on the return leg. And that Leaf driver was nearly ready to pull out when I pulled up next to her at the charging station.

In Coos Bay and Port Orford on the Southern Oregon coast, curious passersby approached. “You’re the first person I’ve ever seen using this public charging station," one said with wonder.

Several said they approved of my non-polluting chariot, but none were ready to go all-electric themselves.